Tehran, YJC. US Federal Court has ruled that Iranian archeological objects in Chicago museums remain belonging to Iran despite plead by Israeli entities.

Following a bombing in a shopping center in Jerusalem, some Israelis

filed a suit in which they demanded to be given the Achaemenid archeological objects,

which are currently in museums of Chicago, US, for archeological studies, as recompense.

On Friday March 28, the US Federal Court ruled against the plead

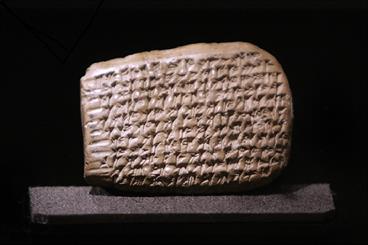

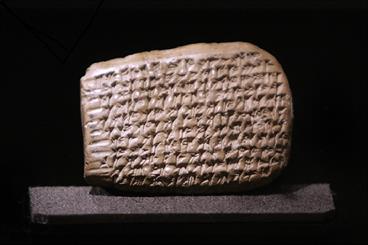

made by the Israelis and maintained that these objects which include Achaemenid

tablets remain as assets of Iran.

In 1933 the German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld (1879-1948) who was excavating

at Persepolis (the famed Achaemenid palace complex in southwest of Iran) under

the sponsorship of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, found 2

small rooms filled with cuneiform tablets and fragments.

In those days, tweets were called telegrams. So, Herzfeld sent a

telegram from Shiraz (the closest city to Persepolis) to James Henry breasted,

the legendary American director of the Oriental Institute, who was in Cairo,

Egypt, at the time: "Hundreds Probably thousands business Tablets Elamite

Discovered on Terrace. Herzfeld” 84 characters (with spaces). Perfect.

2013, the year of the historic Cyrus Cylinder tour in U.S. was also

the 80th anniversary of the discovery and recovery of the Achaemenid

administrative archives at Persepolis-the Persepolis Fortification Archive and

the Persepolis Treasury Archive.

The tablets were lent out to the Oriental Institute by the Persian

royal authorities, and 2,353 small boxes were shipped to Chicago for further

research.

And so the ancient archive travelled from the Highlands of Persia

to Chicago-the windy city.

The tablets at the Oriental Institute, collectively known as the

Persepolis Fortification Archive, have kept the company of a handful of

Elamitologists in the long winter nights and in the summers since 1936-except

for a break during the Second World War (1939-1945).

A small group of pioneering American scholars, including George

Cameron (1905-1979) and Richard Hallock (1906-1980), worked patiently over

decades editing these obscure Elamite texts, establishing their underlying

scribal practices, methodically interpreting them and in the process partially

reconstructing difficult (and still obscure) Elamite language, while others

worked on the few hundred tablets with Aramaic texts found with them.

There were also thousands of seal impressions-sort of ancient

signatures-on these tablets, which according to some scholars, were "the making

of a new museum of Achaemenid Art.” Start of a beautiful thing.

Contrary to the popular myth that these clay tablets were

fire-baked when Persepolis was torched in 331 BCE by the Macedonian King Alexander

III (336-323 BCE) as the symbol of the Persian power, they survived mostly

un-baked like many other clay tablets. The fire, however, caused parts of the

fortification wall to collapse on top of the tablets, letting them live to tell

about a small part of the vast Persian way of life in and around the Persian

heartland.

They turned out to be humdrum administrative accounting records-the

details of the storage and distribution of foodstuffs and livestock from the

lands around Persepolis.

Ancient bureaucratic paperwork in duplicates and triplicates!

When Richard Hallock, another master of understatement, finally

published his Persepolis Fortification Tablets (Chicago,

1969) leading to a renaissance in Achaemenid studies down the road, he modestly

described the foundation of his pioneering work as "The Achaemenid Elamite

texts found at Persepolis add a little flesh to the picked-over bones of early

Achaemenid history.” 121 tweetable characters (with spaces).

In 1933 the German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld (1879-1948) who was excavating

at Persepolis (the famed Achaemenid palace complex in southwest of Iran) under

the sponsorship of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, found 2

small rooms filled with cuneiform tablets and fragments.

In 1933 the German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld (1879-1948) who was excavating

at Persepolis (the famed Achaemenid palace complex in southwest of Iran) under

the sponsorship of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, found 2

small rooms filled with cuneiform tablets and fragments.